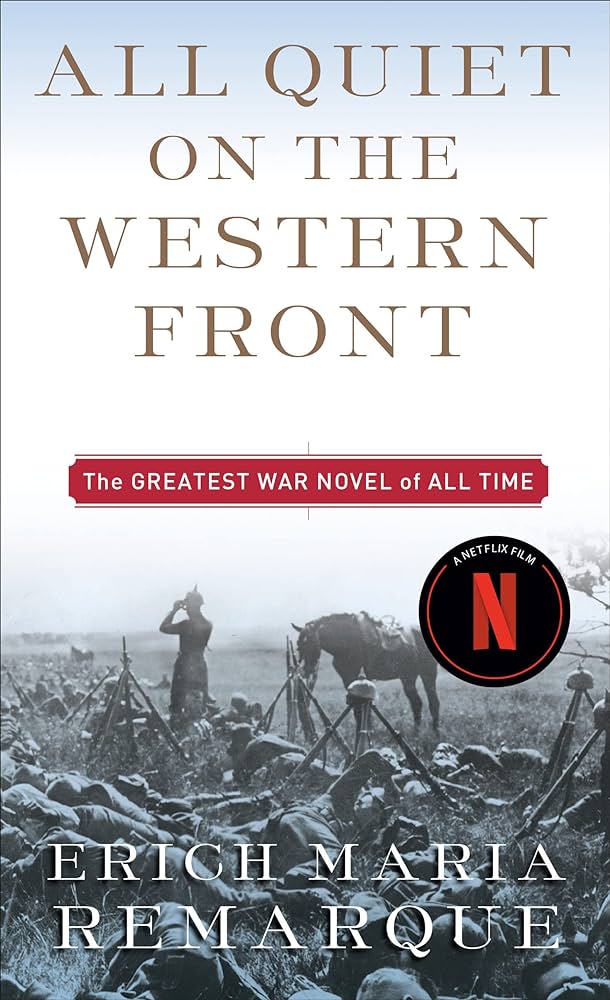

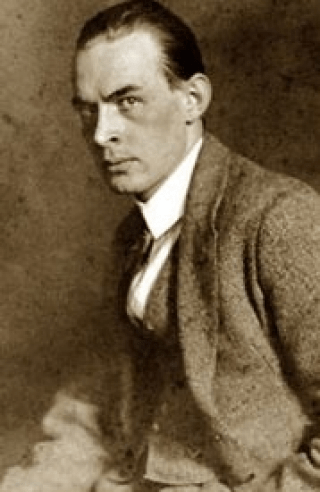

All Quiet on the Western Front, a novel published in 1928 by German writer Erich Maria Remarque, belongs to the classics of pacifist literature. Inspired by the author’s own experiences in the First World War, the book is written as a fictional first person narrative of Paul Bäumer, a young German soldier fighting on the Western front. Paul volunteered to join the army, together with his entire high school class, under the influence of a patriotic teacher.

Through the eyes of Paul, Remarque tells the tragic story of Germany’s lost generation of young men who, traumatised by the senseless brutality of trench warfare, would not have been able to return to normal life even if they somehow managed to survive the four-year-long carnage of the First World War. This loss of innocence is brilliantly conveyed in a poignant episode when Paul briefly returns home on convalescent leave. In fact, although the book contains many graphic depictions of death and injury, Paul’s inability to talk about frontline experiences with his parents and his failure to conjure any feelings when reading a book that used to be his favourite are probably the most hauntingly depressing scenes in the whole novel.

Alienated from relatives and friends who were unable to comprehend the horrors of industrialised warfare, Paul found solace only among other soldiers. The importance of frontline camaraderie for preserving life and maintaining sanity in the face of omnipresent death is emphasised in the novel’s comical interludes which show Paul and his comrades engaging in various escapades in search of food and local girls. The simple form and mundane content of Paul’s narrative give Remarque’s novel a feeling of unpretentious authenticity that contrasts favourably with the pathos of most anti-war books and films.

Because of its implicitly pacifist message, All Quiet on the Western Front was condemned by the Nazis who glorified German war effort in the First World War. Remarque’s novel was banned in Germany after Hitler’s rise to power and in May 1933 copies of the book were publicly burned by fanatical German students. Remarque himself was vilified in Nazi propaganda as a traitor, but he managed to escape from the Third Reich and lived in exile in Switzerland and the USA.

Remarque’s famous anti-war novel has been adapted into film three times. The American adaptation from 1930 won two Oscars, including for Best Film, and greatly influenced the way in which the First World War has been remembered in the West. The latest movie, a German-language version directed by Edward Berger and starring Felix Kammerer in the role of Paul Bäumer, was released in cinemas in 2022 and is now available on Netflix. Berger’s All Quiet on the Western Front was nominated to nine Oscars and won four: Best International Film, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score and Best Production Design.

Interestingly, despite its huge international success, the film met with many negative reviews in Germany, where it was criticised for historical inaccuracy and deviation from the original source material. In fact, Berger’s film has very little in common with Remarque’s novel apart from the title and names of main characters. While the book deals with experiences of ordinary soldiers in World War I, the movie adds a new – and in my opinion rather unnecessary – subplot about German politician Matthias Erzberger (played by Daniel Brühl) who signed the armistice on 11 November 1918. What is more, the ending of the film is completely different from the book and actually changes the whole meaning of Remarque’s story. In the novel, the main hero recognizes the humanity of the enemy and realises that German and French soldiers are brothers who share the same fate. In Berger’s film, the Germans and the French are so filled with hatred that they kill each other with bare hands until the very last minute of the war.

The contrast between the book and the film possibly reflects two different methods of presenting an anti-war message. Remarque’s novel is a nuanced depiction of authentic wartime experience which conveys its pacifist lesson in a subtle, almost subliminal way. Berger’s film shocks the viewer with a crescendo of historically inaccurate but visually striking scenes that expose the war’s dehumanising effect on soldiers.

Which approach do you find more appealing to modern audiences?