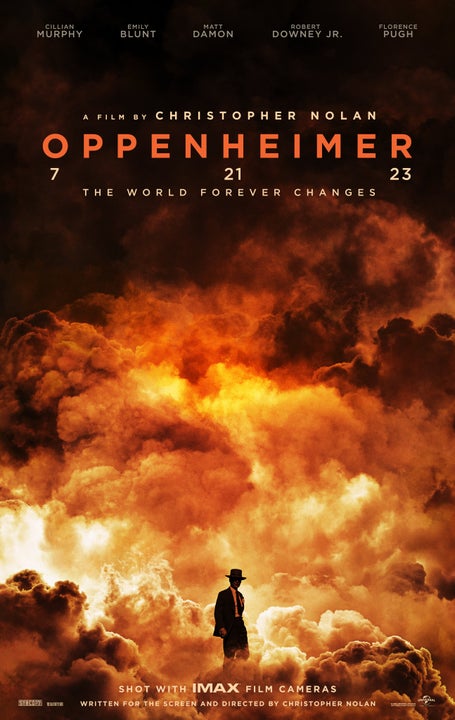

On 6th and 9th August 1945 the United States of America dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a turning point in history that has forever changed the nature of war. By unleashing the power of nuclear chain reaction to produce weapons of mass destruction, American scientists made the annihilation of the whole world a theoretical possibility. This is the central message of Christopher Nolan’s new film Oppenheimer.

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

J. Robert Oppenheimer (played by the Irish actor Cillian Murphy) was an American theoretical physicist of German Jewish origins who during the Second World War directed the Los Alamos Laboratory where the first nuclear weapons were developed as part of the so-called Manhattan Project. Known as the “Father of the Atomic Bomb”, Oppenheimer is the eponymous hero of Nolan’s three-hour long movie which is composed of two intertwining plotlines. The first one, entitled “Fission” and shot in colour, deals with Oppenheimer’s pre-war scientific career and wartime involvement in the Manhattan Project. The second plotline, entitled “Fusion” and shot in black-and-white, focuses on Oppenheimer’s post-war opposition to the development of a hydrogen bomb (an even more destructive form of nuclear weapons) and the ensuing political intrigues in the McCarthy era. The two plotlines culminate in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and the United States Atomic Energy Commission’s revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance in 1954 due to his past association with Communists.

The film shows how Oppenheimer and other left-leaning scientists from the Radiation Laboratory of the University of California at Berkeley initially wanted to develop an atomic bomb to prevent German Nazis from completing their own nuclear weapons programme ahead of the Allies. In the end, however, the Third Reich had been defeated a couple of months before the American scientists completed their tests at Los Alamos. Despite some half-hearted attempts by Oppenheimer and his colleagues to prevent the actual use of their deadly creation, the Truman administration decided to drop atomic bombs on Japan.

The most striking sequence of the movie starts with the successful detonation of a test nuclear weapon in the deserts of New Mexico on 16 July 1945. Shots depicting wild jubilations of Manhattan Project scientists are immediately followed by a scene where we can see how the military takes over the two remaining bombs. Oppenheimer is left out of the decision-making process and finds out about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki only from the radio. Nolan captures perfectly the arrogance and political naivete of the scientists who were involved in the development of the atomic bomb. The British director’s film follows here in the footsteps of great literary works that have also dealt with the responsibility of scientists for how their work will be used. What came to my mind while watching Oppenheimer was Mary Shelley’s classic novel Frankenstein from 1818 and Bertolt Brecht’s play Life of Galileo which premiered in 1943 but was rewritten in a more pessimistic tone following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Although I was overall very impressed with the film and would definitely recommend watching it in a cinema, there are some shortcomings that need to be addressed from a historian’s point of view. First of all, I think that a biographical film told from the perspective of a single individual is not the best way of showing how the nuclear weapons were first developed and used. Even though Oppenheimer frequently alludes to the broader context of the Manhattan Project, what is really missing from Nolan’s film is the perspective of the Japanese victims of the atomic bomb. The effects of radiation from nuclear tests in New Mexico on the local Native Americans are also hardly mentioned in the movie. While I can surmise the artistic reasons for not including such scenes in a story that is written from Oppenheimer’s subjective point of view, I believe that Nolan missed here the opportunity to fully confront the modern audience with the terrible consequences of using nuclear weapons.

Paradoxically, therefore, the film’s main weakness is its historicity. Nolan reconstructs the actual events in meticulous detail, largely based on a Pulitzer prize-winning biography by Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird, and some of the dialogues are taken verbatim from transcripts of Oppenheimer’s 1954 security hearing which were made public in 2014 by the US Department of Energy. This is why, when asked in the movie about the number of causalities caused by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer gives the low estimate of 70,000, even though we now know that the actual death toll might have been as much as five times higher (up to 350,000 victims). The film likewise fails to mention the long-term effects of radiation poisoning on the Hibakusha (survivors of the bomb) and their children.

What is more, in a scene depicting a meeting between Oppenheimer and the Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, understandable reservations against dropping atomic bombs on civilian targets in Japan are rather easily dismissed with the worn-out argument that forcing Japan to surrender would save the lives of thousands of American soldiers. We now know that Japan was about to surrender anyway and that the Truman administration’s decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 had more to do with intimidating the Soviet Union on the eve of the emerging Cold War. In fact, there were important figures in the American political and military establishment, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower, who opposed the use of nuclear weapons against Japan.

Incorporating the current state of knowledge into the script would not only set the historical record straight, but would also cast even more doubt on the integrity of Oppenheimer and other scientists who were “just doing their job” in the American nuclear programme. In a memorable scene inspired by his post-war recollections, Oppenheimer – awestruck by the test nuclear explosion he has just witnessed in the deserts of New Mexico – quotes a line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita:

Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

The film’s central message about nuclear energy’s potential to destroy the world is rather subtle and made explicitly clear only in the last scene depicting Oppenheimer’s post-war meeting with Albert Einstein. Because of this subtlety, and perhaps in order not to offend American sensibilities, the film fails to call the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for what they really were – war crimes perpetrated against Japanese civilians.

Oppenheimer shows how nuclear weapons started. But how can we end them?

Very good review. Spot on historically. Americans like to believe that we’ve always been “the good guys”. Such ignorance of history, and such arrogance

LikeLike

[…] music set to the lyrics of the Japanese poet Sankichi Tōge (1917-1951) who was a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Various sacred and secular texts are woven into a musical narrative that depicts the horrors of […]

LikeLike